Barbara Gerke

During my fieldwork in India, and in preparation for this project, I encountered the following explanations of duk (dug), the Tibetan term for “poison,” which in the context of making of medicines means a range of things. The way they are listed here reflects how Sowa Rigpa practitioners (amchi) spoke about them during interviews, informal conversations, and practical demonstrations.

Duk refers to those parts of medicinal substances that (1) would be difficult to digest by the patient, (2) would weaken the potency of other parts of the same substance, (3) are too “rough” or tsup (rtsub) in their potency, or (4) are actually poisonous and would cause symptoms of poisoning in the body. A piece of a bark that is not poisonous or toxic as such can for example be duk, as it would weaken the potency or nüpa (nus pa) of the plant when digested. It is therefore removed as part of the cleaning process in medicine making called dukdön (dug ’don, lit. “expelling poison”), often translated by English-speaking amchi as “purification” or “detoxification,” or simply as ”removing the harmful parts.” A visit to a small private pharmacy, in Tibetan menjorkhang (sman sbyor khang), revealed some of the practical aspects of dukdön.

Dr. Thokmey Paljor welcomed me to his menjorkhang in Salugara, in the foothills near Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, in May 2015. I had known him from his time at the Men-Tsee-Khang, when he was head of the Translation Department. After early retirement, he chose to manufacture medicines and trained privately with senior Men-Tsee-Khang amchi. On one of my previous visits to his residence, I had expressed my wish to visually document his practice of dukdön, to which he happily agreed. He made only herbal compounds, so this was a good opportunity to understand dukdön practices involving plant substances.

Dr. Paljor had prepared several samples to show me the entire range of dukdön of plant materials: fruits, seeds, roots, leaves, flowers, and branches (Fig. 1). While cutting open a piece of chebulic myrobalan fruit (a ru ra), taking out its seed, he explained: “We have to take out the seed. The seed is the poisonous part of the fruit. The seed is the duk. Duk here does not mean a poison or any kind of toxic form. Any part that gives a harmful effect has the name of duk” (Fig. 2). “Does ‘harmful’ here relate to the taste or to digestion?” I asked, feeling the hardness of the seed. “Harmful effect means it harms the digestive system. When the digestive fire—we call it medrö (me drod)—is harmed, the entire bodily constituents are harmed. So, you do not have to relate it to taste. It is the rough part that harms the digestive function,” he explained.

We looked at the seeds of the three types of myrobalan. All of them were hard in texture, but so were the dried fruits. “From all the fruits that are used in Tibetan medicine, all inner seeds have to be taken out. Aru, baru, kyuru [a ru, ba ru, skyu ru, the three myrobalan fruits] are only an example (Fig. 3), There is one exception, nyingshosha (snying zho sha). In this case the seed is the main medicine. You can use all of it, cover and seed, there is no duk” (Fig. 4).

Our conversation transitioned into a discussion on the roughness of duk. “Can you taste the duk?” I asked, knowing that taste was one of the main criteria to investigate the potency of plants. Dr. Paljor explained: “What is mentioned in the text is that the duk parts have the quality of roughness (rtsub). It has nothing to do with taste.”

I touched the myrobalan samples and inquired: “Is roughness detected through touch? The fruits and the pits are both rough by touch. How do they know this is a men and this a duk?” “Yes, how do they know? This is a problem,” he responded. I suggested: “Maybe by experience?” He laughed and explained: “Tibetan medicine was taught by Yutok Yönten Gönpo, who was an incarnation of the Medicine Buddha. The entire Gyüzhi [Four Treatises] was given through the eyes of wisdom, and then just revealed and written down. How can it fail? There were no experiments, no scientific investigations.”

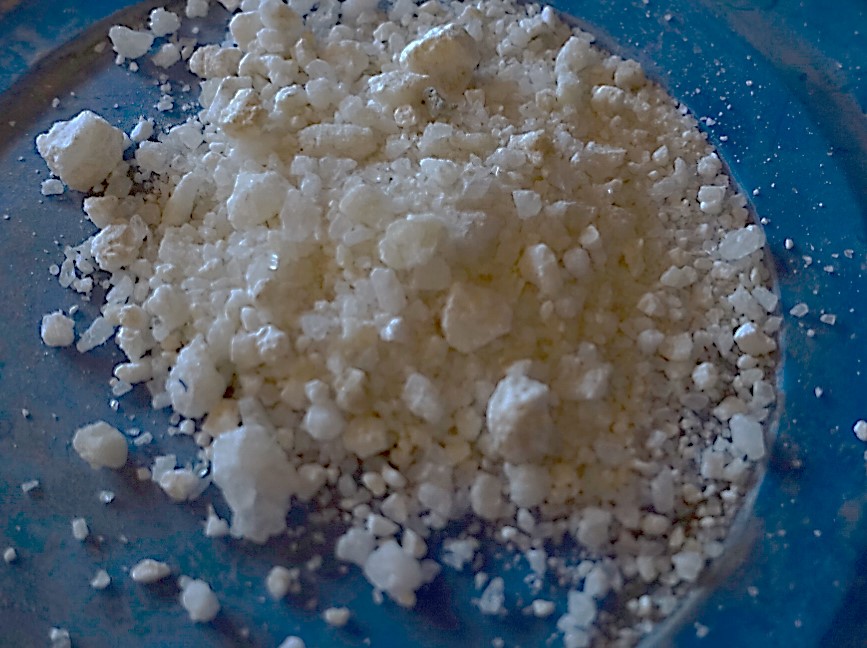

He then showed me four types of roots, where the outer bark had to be peeled off with a pocket knife to remove the duk. With the leaves it is the petiole or stalk (ngar pa), also called stem or yuwar (yu bar), that has the duk and has to be removed. With the flowers it is the tiny sepals that hold the flower buds that are duk. I realized that dukdön is very labor intensive and has to be done by hand. Dr. Paljor has three to four assistants to help with the dukdön. “The aim is to make it smooth,” he said, showing me the smooth surface of the Ashwaganda root (Fig. 5). “Wherever you find duk in herbal substances, all the time there is the same explanation: the roughness has to be made smooth.” Pointing to some white flower petals he had just plucked from their sepals, he explained: “This is already called men, even though the jorwa [sbyor ba = compounding] has not been done, because it has the nüpa inside.”

Then he took a branch from a thorny bush, which was a type of Berberis (skyer pa), a “wood medicine” (shing sman). “I am going to take out the thin outer part of this plant. And then I take out the middle soft spongy part (Fig. 6). The real medicine is the middle part (Fig. 7).” In this case the soft consistency of the pith did not translate into the smoothness of a men, but was considered a duk, just like the outer thorny layer.

Thinking about the typically bitter tastes of poisons, I asked: “If you taste the duk part, would it be bitter?” “Not necessarily. The taste it similar to the good part.” He let me taste a part of kyerpa. It was very bitter. “All of kyerpa is used: fruits, leaves, branches, all are men. Most parts are bitter. Only the fruits have different tastes during different stages of ripening. You cannot taste the duk.”

He then showed me a branch of tikta (tig ta, Swertia chirata) to demonstrate the dukdön of branches (yal ga). “Any branch with nodes has duk, which is the node. Again, even if you use the smaller branches, these are the nodes and they all have to go, all for the same reason, because they are too rough.” (Fig. 8).

None of the samples he showed me were considered poisonous plants. Still, they had duk that had to be removed by hand with hours of hard labor. Only the myrobalan fruits could be purchased without seeds in the herbal markets of Amritsar, where he bought many of his plant materials. The rest had to be done by hand before compounding.

“Roughness” and its opposite “smoothness” are among the seventeen qualities (yon tan bcu bdun). Quite different from to the general practice of Tibetan physicians analyzing the potency of plants by taste, duk does not necessarily depend on taste but on the rough quality of the plant part that would weaken the digestive heat. This perception of roughness does not always depend on texture, as the example of kyerpa showed, where the soft, spongy part was also considered duk.

To summarize some insights from this visit with Dr. Paljor, the sensory evaluation of raw substances used in medicine is based on a variety of factors. Duk, the harmful part in substances, cannot be detected by taste. Its roughness and heaviness are qualities not necessarily visible or tactile, but deemed efficacious in Sowa Rigpa. They need to be made “smooth” for the substance to be potent and digestible. Duk needs to be known in its effect on the body and especially on the digestive heat.

Duk is not always equal to “poison,” and many substances can have various types of duk that can be removed through washing, taking off the bark, and so forth. The practice of dukdön of raw materials is a very important part of Sowa Rigpa menjor practice. It is a form of pre-processing that then allows the mixing of multiple substances into compound medicines that unfold their potency or nüpa in synergistic ways.

All photos are by the author.