By Stuti Singh and Barbara Gerke

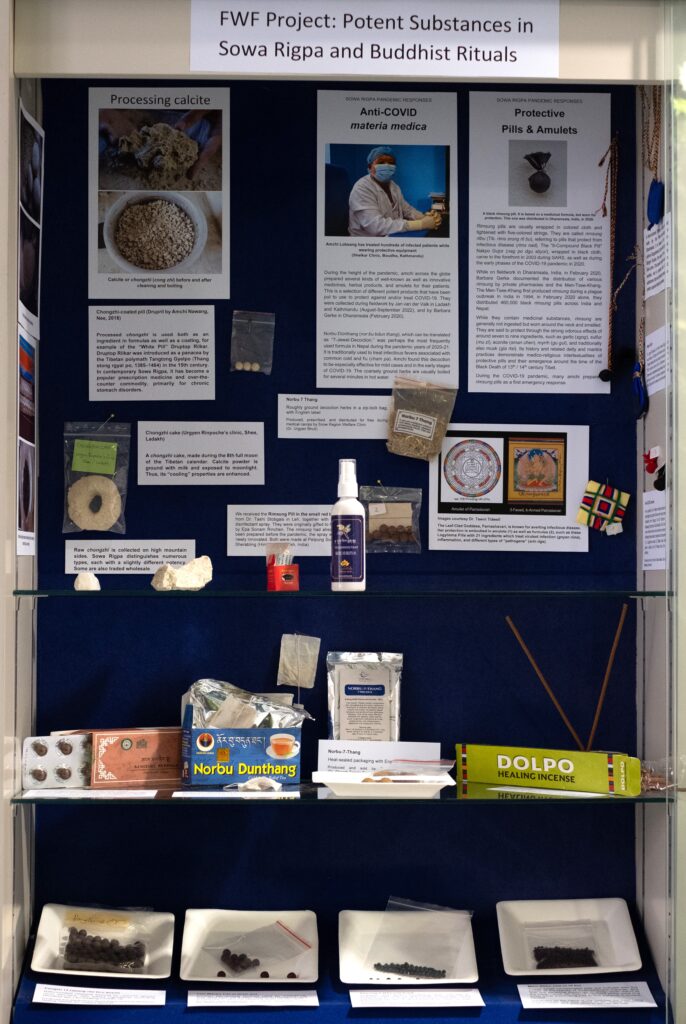

In this blogpost we discuss some of the accessory tools that Stuti Singh came across during her fieldwork with Sowa Rigpa medical practitioners (amchi) in Spiti in the summer of 2023. We present images and explanations of medicine making (menjor) tools that are used to sieve ground-up substances, store, and measure them. We discussed material characteristics of menjor tools while preparing our co-authored article titled Menjor Tools and the Artisanal Epistemology of Making Sowa Rigpa Medicines in Spiti for a forthcoming book on Tibetan Materialities (edited by Emma Martin, Trine Brox, and Diana Lange), currently under review. Here are some of the accessory tools that were not included in the book chapter.

Accessory tools such as sieves, clippers, brushes, spatulas, and pouches play an important role in the preparation of medicine powders among Sowa Rigpa practitioners in Spiti. Amchi primarily prepare powders called chéma (phye ma), which can be turned into round handmade pills called rilbu (ril bu). These tools are passed on across generations, and while their materiality remains, their size, meaning and utility might change in tandem with the changing socioeconomic and climatic environments that amchi find themselves in.

Sieves

Previous generations of amchi used handmade sieves with relatively large holes, whereas the present generation relies on ready-made finer sieves that can filter larger quantities of ground-up materials. In the past, practitioners would often visit patients at their homes, particularly during winter, preparing small amounts of formulas on the spot after diagnosis. They would carry their own tools for this process. Nowadays, marketplaces provide factory-made accessory tools. Amchi have adapted to using what is available in local markets, reflecting both changes in technology and economic factors influencing traditional practices.

Amchi Chhering Dorje from the village of Kibber used a plastic sieve to separate coarse from fine powder and a paintbrush to brush up the powder on the grinding stone (Fig. 1A). Plastic sieves are cheaper and thus more economical for amchi than metal or stainless steel sieves. Amchi Sonam Dorje used a larger plastic sieve (Fig. 1B) but said these plastic sieves are not as good as cotton cloth for filtering coarse substances.

Fox and rabbit legs

Fox or rabbit legs were the traditional brushes before plastic brushes became available. We saw them in both Spiti and Ladakh. Amchi Sonam Dorje from Ka village showed Singh an animal leg brush while grinding medicine for her during a personal consultation (Fig. 2). He explained the use of a rabbit leg in menjor as follows:

“You know, a rabbit has four limbs but it can only use three of them, because the remaining limb was given to the rabbit as a tool for medical practitioners. Therefore, throughout its life a rabbit cannot use it. When a rabbit dies that remaining leg will be used as a tool to brush off the ground-up medicines from the mandah. (…) The rabbit leg does not lose hair, thus it is a perfect brush. However, I am using a fox leg which I got from a dead fox which I found in my water tank in winter. It was almost decomposed and I decided to chop off its legs and use it as a brush for my practice. In Sowa Rigpa we do not waste materials, we have to respect these materials for ethical practice.”

Amchi do not kill animals for these brushes and only use them from dead animals they find in their fields, which is a rare event, Thus most leg brushes are inherited. Rabbit leg brushes are preferred due to their ability of not losing hair. This illustrates how amchi carefully interact with their environment to source material for menjor.

While some tools lose their significance, others are still valued. Amchi Chhering Norbu from Sagnam village inherited a rabbit leg brush and an iron sieve from his father (Fig. 3A and B). He still used the brush, explaining that the rabbit leg does not leave hair in the medicine. However, he prefers using a plastic sieve as it is easily available in the market. Moreover, the sieve hand-crafted by his father is smaller in size. He added that replacing the older sieve with a plastic one preserves his father’s sieve as a valued artifact.

Amchi Lobzang Tanzin from Mane Gogma inherited two hand-made sieves made by his father and kept in his pharmacy. He brought the wood-framed sieve (Fig. 4A) to his house for cleaning raw materials and sieving pounded items. The larger tin sieve (Fig.4B) is no longer in use and was replaced by a plastic one.

Amchi Lobsang Gyatuk from Poh inherited a small circular tin sieve, probably made from a lid, from his father, who had made it by making holes with a hot needle (Fig. 5A). He reflected on the time when his father was practicing:

“In those times, amchi were preparing less amounts of medicines and that there was no concept of preparing stocks of medicine in advance. Therefore, a smaller size sieve was sufficient.”

He does not use it anymore as he now grinds larger amounts of medicines to keep in stock, which requires a bigger stainless-steel sieve (Fig. 5B), which he bought at the local market.

These hand-crafted tools illustrate the different materials available in an amchi’s environment that could be turned into menjor tools. With limited access to machines, they demonstrate amchi skills and ingenuity. A hand-made tin sieve presented an innovation from the earlier cloth sieve, which was then replaced by ready-made plastic and stainless-steel sieves.

Leather bags for storing medicines

Singh also came across hand-made leather bags used to store substances and medicines. They have their own material language. In Spiti, a generation ago it was still common for amchi to sew leather or cloth pouches for storing prepared formulae. Amchi Lobzang Tanzin inherited several khomak and kowa (cloth and leather pouches, Tib. khug ma), which were crafted by his father (Fig. 6A and B). He said:

“When I have to go somewhere and I am supposed to take medicines along with me, then I carry these bags; I can also write the name of the formula on the wooden tags.”

Medicinal powders are stored in plastic or glass containers in the pharmacy of Amchi Sunil Bodh and Amchi Lobsang Gyatuk. In some cases, they prepare hand-rolled pills called rilbu, especially for patients living far away (Fig. 7A). According to them, rilbu have a longer shelf life than chéma, which only last one month.

Amchi Lobsang Gyatuk inherited a yak leather travel bag from his father which was brought from Tibet (Fig. 7B):

“It was brought by a monk of Tabo monastery as he wanted to give something to my father due to his commitment towards Sowa Rigpa practice. Therefore, when he went to Tibet, he brought a huge bag made of yak leather to give to my father. During those days, amchi used to travel long distances, especially during winters, to provide treatment for their patients. Therefore, they had to carry all the necessary raw materials and tools for making medicines.”

When the bag was offered to his father as a gift by the monk, it served as a travel bag. Nowadays it is used for storing materials in the pharmacy. It has transitioned from being a travel bag to a storing bag.

A multi-purpose silver spatula

We can observe a merging of properties in the multi-purpose silver spatula of Amchi Sonam Dorje, which he inherited from his father-in-law, who was his teacher (Fig. 8). This tool is unique in that it is used for measuring medicines, grating bones for use in medicine (through its rough surface), as well as for applying moxibustion. It is made from silver, which is considered a precious substance and safe to use with medicines. Amchi Sonam Dorje does not use it for grating anymore in order not to damage it, and rarely uses it for moxibustion. While packing a one-week dose of a formula for a patient, Amchi Sonam Dorje used this silver spatula. He added: “I always use this spatula for measuring the amount of medicine for my patients.”

All menjor tools tell us stories of transformation, migration, beliefs, and practices. Tools are a medium of passing embodied knowledge to the next generation of amchi. In particular, the accessory tools introduced here have evolved over time in Spiti, some being repurposed. Several amchi preserve menjor tools of previous generations as a legacy of their lineage, taking us back to when practitioners had very scarce resources but a broad set of skills that allowed them to hand-craft what they required. Some of these tools were able to maintain their utility in contemporary Sowa Rigpa practice, while others can be interpreted as surviving witnesses of a waning tradition of highly innovative self-sufficiency.