University of Copenhagen, 12-13 May 2022

Authored by Barbara Gerke & Jan van der Valk

This Tibetan Materialities Workshop took place in Copenhagen (May 12-13, 2022) in preparation for a panel at the forthcoming 16th IATS Conference in Prague (July 3-9, 2022). Twelve scholars met across disciplines at the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies. Emma Martin (University of Manchester), Diana Lange (University of Hamburg) and Trine Brox (CCBS, University of Copenhagen) co-organized this workshop with the aim to create an international collaborative forum on Tibetan materialities. Funded by the Asian Dynamics Initiative, the group took advantage of this opportunity to steer discussions and stimulate research, reflection, and writing.

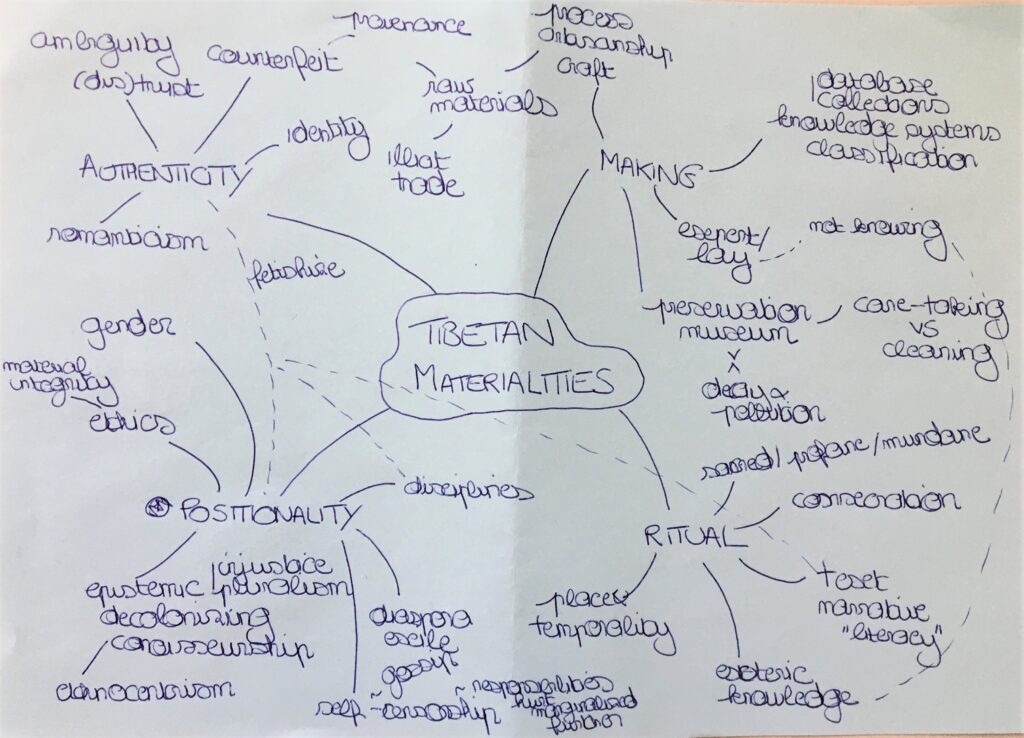

We (Barbara and Jan) were the invited discussants, Trine Brox the local host. The nine presentations illustrated the broadness of approaches that Tibetan and Himalayan objects and artefacts have recently attracted in different disciplines (e.g., Museum Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Sociology, and Conservation Studies). We covered locally embedded preservation practices of statues at the Namgyal Institute for Tibetology in Sikkim (Katia Thomas), and how to decolonize the narratives and classifications of Tibetan collections at the British Museum in London (Chukyi Kyaping). What can we learn from local artisans and rituals to overcome the limits of modern/secular museum descriptions? How do artefacts change over time, how to explore the question of their “origins” and rightful owners when we find a human skull cup in a museum collection and begin linking it to a living tantric tradition across the Himalayas and beyond (Ayesha Fuentes)? How to craft a critical museology of dissent amidst Chinese-Tibetan politics and exile activism when giving advice for the layout and display of the Tibet Museum in Dharamsala (Emma Martin)? How to integrate noninvasive spectroscopic analysis of pigments – thus treating maps as material sources – to learn more about Tibetan map-making traditions and at the same time make sense of undergirding cosmologies, for instance when finding a mandala on the back of Tibetan map (Diana Lange)? How do the embodied meanings and practicalities of wearing Tibetan Buddhist robes change for ordained Western nuns in rather isolated circumstances in Britain (Caroline Starkey)? How does participant observation, knowing by doing, and also not knowing by missing out on asking pertinent questions during fieldwork that we could not or did not follow up on, lead to “patchwork ethnography” and the forgetting of untold stories. How does what do we NOT write about impact our ethnographic narratives (Mark Jeffrey Stevenson)?

Locality, powerful spaces, and potent landscapes were recurring themes when approaching the social and political meanings of Tibetan objects and their use in every-day lives, whether in a contested Tibeto-Japanese Buddhist temple setting in Nagoya (Steven Cristopher), or among women and their menstrual practices in and around Vajrayoginī ritual sites in Sankhu, Nepal (Sierra Humbert).

The intertwining of narratives and material practices becomes more complex, blurred, and conflicting when rumors, sensitive topics, sacred/secret knowledge, “incomplete” fieldwork, and serendipity are taken into account. This also raises questions on research ethics, when and how to ask questions, and what to publish—or not. Discussions on representation, authenticity, “truth,” and dissent made us reflect on our positionalities, individually as researchers in specific settings as well as collectively as a group engaging with critical issues within Tibetan Studies. We talked about how we find our theoretical and methodological inspiration to explore all these interdisciplinary questions in other disciplines—rarely in Tibetan Studies itself. Does this place us at the periphery of Tibetan Studies, and/or Tibetology at the margins of Tibetan and Himalayan material-based research? Barbara had to think of Janet Gyatso’s first Aris lecture “Beyond Representation and Identity,” in 2015. Her question still rings in her head all these years later:

“How many times has anyone outside of Tibetan Studies—even people in as closely aligned fields as Indology or Sinology—cited any book or article in Tibetan Studies for an insight or principle or pattern or concept or mode of analysis that is relevant to their own work?”

Realizing that we search in other disciplines for modes of analysis, the question arose: How can this materiality research group contribute to the development of Tibetan Studies? Participants noted the limitations of the dominant textual-philological focus and methods of Tibetan Studies, especially when it comes to researching materially mediated skills and practices.

Our aspiration to work across the boundaries of disciplines in the context of Tibetan materialities involves critical thinking and coming up with new conceptual frameworks. Engaging Tibetan objects and their varied meanings and potencies inspires us to continually question peoples’ and our own perceptions, ideas, and practices. As a group we aspire to make our work more visible and create more opportunities for cross-fertilization, such as the upcoming IATS panel, an edited volume, and further online and in-person meetings. We both enjoyed these two days of cross-disciplinary synergy and intellectual exchange, and look forward to how this is going to evolve.